Even after the previous installment of this series, there are still people who believe that calorie intake—and calorie output via exercise—are the only factors that affect weight loss. Apparently my work is not done!

(This is a multi-part series. Go back to Part I, Part II.)

Empirical Evidence: A Calorie Is Not A Calorie When You Add Lots Of Coconut Oil Or Butter To Your Regular Diet

Take three groups of Wistar rats. One group gets free access to standard low-fat rat chow; the others get free access to both standard chow and a “high-fat chow”, 2/3rds of which is butter or coconut oil. (Hat tip to George Henderson for this one.)

Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007; 4: 4.

Long term highly saturated fat diet does not induce NASH in Wistar rats

Caroline Romestaing, Marie-Astrid Piquet, Elodie Bedu, Vincent Rouleau, Marianne Dautresme, Isabelle Hourmand-Ollivier, Céline Filippi, Claude Duchamp, and Brigitte Sibille

(Note: link is to fulltext.)A fourth group of rats in this study ate a methionine- and choline-deficient diet, which was the primary subject of the study (a successful attempt to give rats fatty liver). Short version: deficiencies caused fatty liver, but massive fat ingestion (and “calorie surplus”) did not.

Unsurprisingly, the rats with free access to the rat version of buttered popcorn ate it. By the end of the diet, both the coconut and butter groups were consuming slightly more high-fat chow than regular chow, the butter group was consuming 30% more “calories” than the chow-only group, and the coconut oil group was consuming 140% more “calories” than the chow-only group!

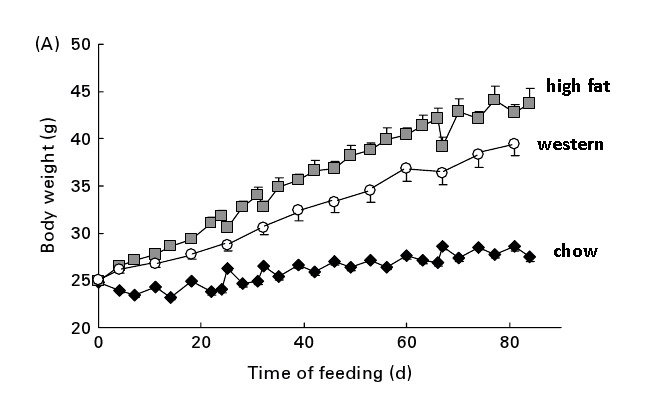

If a calorie is a calorie, we would expect the rats to gain fat roughly in proportion to their calorie intake. Here’s what actually happened, from Figure 1:

Figure 1 from Romestaing et.al.

The open triangles and dashed line represent the chow-only rats, the gray circles and solid line represent the butter+chow rats, and the black circles and solid line represent the coconut oil+chow rats.

Results: “Surprisingly, in spite of a larger energy intake, body mass was not affected in rats fed the high fat diets.” The chow+coconut oil rats ate 2.4 times as many “calories” as the chow-only rats—

—and gained exactly the same amount of weight.

Even the butter+chow rats ate 30% more “calories”, but gained only a non-significant amount of extra weight.

Errata?

Note that the graph above is partially incorrect: Table 3 gives calorie counts for each group, which agree with the figures quoted in the Results section but disagree with the graph. Apparently the calorie curve for the chow-only rats is shifted upwards, and the calorie curve for the butter+chow rats is just plain wrong! (Or Table 3 is wrong…I’ll pass on any additional information I find.)

Why It’s Important To Report Absolute Change, Not Just Relative Change

The study makes much of the extra WAT (white adipose tissue) gained by the coconut oil+chow rats—62% more—but as the rats started with very little fat, the total gain was approximately 8.4g versus 5.6g for the chow-only rats, for a difference of appx. 2.8g of fat on a 450-gram rat.

In human terms, that’s a 0.6% difference in bodyfat percentage…just under a pound for a 160-pound human.

This, gentle reader, is why it’s important to look at absolute percentages, not just relative percentages…a 62% increase in almost zero is still almost zero. (And this is why so many drug trials report relative risk…a 40% decrease in mortality sounds great until you discover that your absolute risk dropped from 1 in 200 to 1 in 333. Meanwhile, the chance of harmful side effects has stayed the same—and it’s usually far greater than the chance of being saved.)

Conclusion: A calorie is not a calorie when you add lots of coconut oil or butter to your regular diet.

Empirical Evidence: A “Calorie” Of Almonds Does Not Equal A “Calorie” Of Complex Carbohydrates

Take 65 obese and insulin-resistant people. Divide them into two groups, and place each group on a different 1000-calorie starvation diet for 24 weeks. (Another hat tip to Kindke for bringing this one to my attention.)

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Nov;27(11):1365-72.

Almonds vs complex carbohydrates in a weight reduction program.

Wien MA, Sabaté JM, Iklé DN, Cole SE, Kandeel FR.

(Fulltext available here.)

The study subjects were in bad shape. Mean BMI: 38, weight: 250# (113kg), fasting blood glucose: 152 mg/dl, fasting insulin: 46 ulU/ml (320 pmol/l). Note that a reasonable fasting glucose measurement would be <100 mg/dl, and reasonable fasting insulin would be <9 ulU/ml...so these subjects exhibit classic signs of the metabolic syndrome in addition to being obese.

Now, here comes the interesting part: Just over half the 1000 calories were fed as either "self-selected complex carbohydrates" ("peas, corn, potato, pasta, rice, etc.") or as unsalted, unblanched almonds. I'll skip to the punchline:

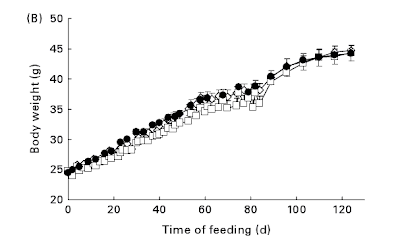

[caption width="400" align="aligncenter"] Figure 2 of Wien et.al.[/caption]

Figure 2 of Wien et.al.[/caption]

That’s 43 pounds lost (19.5kg) for the almond group versus 26.6 pounds lost (12kg) for the complex carbohydrate group.

The authors quote, with typical scientific understatement: “The difference in weight loss was unexpected, given the study design featuring a matched prescribed total calorie intake and equivalent levels of self-reported physical activity between the groups.”

Furthermore, we can see that the “complex carbohydrate” group had plateaued by week 16 (92% of total weight loss after 67% of the time), whereas the almond group was continuing to lose weight at the end of the study (only 77% of weight loss after 67% of the time).

“Calorie math” says that to lose 16.4 more pounds, the almond group would have to have eaten 340 fewer “calories” per day…that’s 2/3rds of the “calories” in the almonds!

Even if we only count the 11.1 pound difference in fat mass lost (see Table 3), “calorie math” requires the almond group to have eaten 230 fewer “calories” per day.

Yet the subjects were voluntary inpatients at a medical clinic, where access to food was controlled. Additionally, “Subjects did not differ in their self-reported evaluation of the acceptability of their assigned dietary intervention in terms of satiety, palatability and texture at weeks 0, 8, 16 and 24,” and “Both groups had equivalent levels of noncompliance…during the 24-week intervention.” So cheating by either group seems unlikely, unless you posit that almonds give you the magical ability to jog for half an hour every day without anyone else noticing—and lie about it.

There were dramatic improvements in health markers for the almond group, which I’ll leave as an exercise for my readers. (Hint: see Table 3.)

Conclusion: A “calorie” of almonds does not equal a “calorie” of complex carbohydrates.

Our Story So Far

Using peer-reviewed science and publicly available population-level statistics, we’ve proven that:

- A calorie is not a calorie when you eat it at a different time of day.

- A calorie is not a calorie when you eat it in a differently processed form.

- A calorie is not a calorie when you eat it as a wholly different food.

- Controlled weight-loss studies do not produce results consistent with “calorie math”.

- “Calorie math” doesn’t work for weight gain or weight loss.

And, therefore:

The juggernaut continues to roll! Continue to Part IV, Protein Matters…and feel free to stir up some controversy by sharing this article with the widgets below.

Live in freedom, live in beauty.

JS

(This is a multi-part series. Go back to Part I, Part II.)

Thanks to everyone who places their Amazon.com orders through my affiliate link: you’re supporting gnolls.org at no cost to yourself. So next time you’re placing an order for books, music, video games, TVs, cooking implements, or anything else, please consider starting here, or at the link in the right sidebar. (Which takes you to the page for The Gnoll Credo—but you can order anything you want, and it’ll still help support gnolls.org.)

To those worried about privacy: no, I have no way to find out who ordered what.