Favorite Articles of the Moment

Disclaimer

• Your life and health are your own responsibility.

• Your decisions to act (or not act) based on information or advice anyone provides you—including me—are your own responsibility.

Recent Articles

-

We Win! TIME Magazine Officially Recants (“Eat Butter…Don’t Blame Fat”), And Quotes Me

-

What Is Hunger, and Why Are We Hungry?

J. Stanton’s AHS 2012 Presentation, Including Slides

-

What Is Metabolic Flexibility, and Why Is It Important? J. Stanton’s AHS 2013 Presentation, Including Slides

-

Intermittent Fasting Matters (Sometimes): There Is No Such Thing As A “Calorie” To Your Body, Part VIII

-

Will You Go On A Diet, or Will You Change Your Life?

-

Carbohydrates Matter, At Least At The Low End (There Is No Such Thing As A “Calorie” To Your Body, Part VII)

-

Interview: J. Stanton on the LLVLC show with Jimmy Moore

-

Calorie Cage Match! Sugar (Sucrose) Vs. Protein And Honey (There Is No Such Thing As A “Calorie”, Part VI)

-

Book Review: “The Paleo Manifesto,” by John Durant

-

My AHS 2013 Bibliography Is Online (and, Why You Should Buy An Exercise Physiology Textbook)

-

Can You Really Count Calories? (Part V of “There Is No Such Thing As A Calorie”)

-

Protein Matters: Yet More Peer-Reviewed Evidence That There Is No Such Thing As A “Calorie” To Your Body (Part IV)

-

More Peer-Reviewed Evidence That There Is No Such Thing As A “Calorie” To Your Body

(Part III)

-

The Calorie Paradox: Did Four Rice Chex Make America Fat? (Part II of “There Is No Such Thing As A Calorie”)

-

Interview: J. Stanton on the “Everyday Paleo Life and Fitness” Podcast with Jason Seib

|

(This is a multi-part series: click here for the index.)

It is the 21st century. We have telephones that fit in a watch pocket, we can sequence the genetic code of life itself, and we can sift the accumulated knowledge of centuries in fractions of a second using Internet search engines. Yet we still don’t understand enough about human biochemistry to create a pill that stops us from eating without causing heart valve defects or uncontrollable diarrhea.

Diet pill’s icky side effects keep users honest, msnbc.com, 7/6/2007

“I’ve pooped my pants 3 times today, and sorry to get descriptive but it even leaked onto the couch at one point!”

“Ya know how when you start moving around in the morning ya pass a little gas. Well, I did and then went into the bathroom and to my horror I had an orange river of grease running down my leg.”

Do Diet Drugs Work?, The Telegraph, 4 May 2009

“I’ve done it. I figured out the secret behind the Alli pills. It’s fear…It’s amazing how the thought of suffering faecal incontinence can create rock solid will-power.”

Clearly I’m in the wrong business: writing life-changing books and articles about how to stay fit and healthy is far less profitable than selling drugs that make people crap their pants.

Meanwhile, in the absence of the magical anti-hunger pill, everyone seems to have their own concept of how to defeat hunger—and thousands of diet books published every year claim that we are simply deficient in everything from acai berry extract to “resistant starch” to the urine of pregnant women. Obviously this is all baloney, because we’re fatter and sicker than ever…

…so let’s back up a few steps and ask ourselves a simple question: “Why are we hungry?”

To answer this, we need an answer to an even simpler question:

“What is hunger?”

Disassembling Hunger and Appetite

To most dieters, hunger is a crafty, insidious demon whispering sweet nothings in our ears.

"Pringles are delicious, and you can stop eating them any time you want." Yet much of the published research, and most of the popular discourse, simply dismisses hunger as an annoying inconvenience—an atavistic, mildly embarrassing instinct that we must rise above in order to maintain our health.

This is completely untrue. Hunger is a normal and necessary human drive, and it serves a very important function: to cause us to find and ingest the nutrients we need to survive. Yet to understand hunger, we must break it down into its components, because:

Hunger is not a singular motivation: it is the interaction of several different clinically measurable, provably distinct mental and physical processes.

Until we understand this, we are doomed to perpetual confusion over our own motivations and desires—let alone others’ writings and recommendations on how to successfully deal with them.

I’ve addressed this subject before, in my very popular article Why Snack Food Is Addictive, which (among other things) explains the concept of “food reward”. What I’m doing here is creating a theoretical framework that allows us to go even farther—by understanding the concept of hunger.

Components of Hunger: Liking Vs. Wanting

We know that liking something and wanting something are not the same thing. I like prime rib, but I don’t want any right now, because I just ate.

Miraculously, the scientific literature often uses helpful and descriptive English words when describing components of hunger. “Liking” and “wanting” are part of the official scientific lexicon: “liking” is a measurement of the pleasure we experience upon eating, i.e. palatability, and “wanting” is a measurement of the relative motivation to acquire and ingest a food.

It turns out that “liking” and “wanting” produce specific patterns of activity in the human brain!

Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior

Volume 97, Issue 1, November 2010, Pages 34-46

Hedonic and motivational roles of opioids in food reward: Implications for overeating disorders

Susana Peciña and Kyle S. Smith

Food reward can be driven by separable mechanisms of hedonic impact (food ‘liking’) and incentive motivation (food ‘wanting’). Brain mu-opioid systems contribute crucially to both forms of food reward. Yet, opioid signals for food ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ diverge in anatomical substrates, in pathways connecting these sites, and in the firing profiles of single neurons.

Brain Research Volume 1350, 2 September 2010, Pages 43-64

The tempted brain eats: Pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders

Kent C. Berridge, Chao-Yi Ho, Jocelyn M. Richard and Alexandra G. DiFeliceantonio

“Liking” mechanisms include hedonic circuits that connect together cubic-millimeter hotspots in forebrain limbic structures such as nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum (where opioid/endocannabinoid/orexin signals can amplify sensory pleasure). “Wanting” mechanisms include larger opioid networks in nucleus accumbens, striatum, and amygdala that extend beyond the hedonic hotspots, as well as mesolimbic dopamine systems, and corticolimbic glutamate signals that interact with those systems.

As we’d expect, “liking” tends to stay more stable over time, whereas “wanting” tends to change dynamically, being a measure of one’s desires at that moment:

Physiology & Behavior Volume 90, Issue 1, 30 January 2007, Pages 36-42

Is it possible to dissociate ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ for foods in humans? A novel experimental procedure

Graham Finlayson, Neil King and John E. Blundell

Findings indicate a state (hungry–satiated)-dependent, partial dissociation between ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ for generic food categories. In the hungry state, participants ‘wanted’ high-fat savoury > low-fat savoury with no corresponding difference in ‘liking’, and ‘liked’ high-fat sweet > low-fat sweet but did not differ in ‘wanting’ for these foods. In the satiated state, participants ‘liked’, but did not ‘want’, high-fat savoury > low-fat savoury, and ‘wanted’ but did not ‘like’ low-fat sweet > high-fat sweet. More differences in ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ were observed when hungry than when satiated.

This would indeed seem to be the common-sense result, but it’s important to understand that liking vs. wanting are not just theoretical constructs: they are distinct biochemical processes.

These motivations don’t just apply to food: any experience we “like” is capable of producing a “want” for more. I discuss this at length in Part VIII.

Components of Hunger: Satiation Vs. Satiety

We also know that the factors which make us stop eating (satiation) are different than the factors that cause us to feel hungry or not hungry (satiety). If all I have available to eat is cotton candy, I’ll soon be satiated, with no desire to eat more—but I won’t experience satiety, because I’ll still be hungry for real food.

Like the terms “liking” and “wanting”, “satiation” and “satiety” have specific meanings in the scientific literature, though according to the dictionary they are synonyms.

Interestingly, French distinguishes them in the same way scientists do: “rassasiement” = satiation, “satiété” = satiety.

Also like the terms “liking” and “wanting”, “satiation” and “satiety” are distinct and reproducible drives:

Nutrition Bulletin Volume 34, Issue 2, pages 126–173, June 2009

Satiation, satiety and their effects on eating behaviour

B. Benelam

Satiation and satiety are controlled by a cascade of factors that begin when a food or drink is consumed and continues as it enters the gastrointestinal tract and is digested and absorbed. Signals about the ingestion of energy feed into specific areas of the brain that are involved in the regulation of energy intake, in response to the sensory and cognitive perceptions of the food or drink consumed, and distension of the stomach. These signals are integrated by the brain, and satiation is stimulated. When nutrients reach the intestine and are absorbed, a number of hormonal signals that are again integrated in the brain to induce satiety are released.

Physiol Behav. 1999 Jun;66(4):681-8.

Palatability affects satiation but not satiety

De Graaf C, De Jong LS, Lambers AC.

The results showed that the ad lib intakes of the less pleasant and unpleasant soups were about 65 and 40% of the intake of the pleasant soup. Subjects ingested about 20% more soup when the subjects had to wait for the test meal about 90 min, compared to the 15 min IMI condition. The availability of other foods had no effect on the effect of pleasantness on ad lib intake. There was also no effect of the pleasantness on subsequent satiety: hunger ratings and test meal intake were similar after the three standardized soups. One conclusion is that pleasantness of foods has an effect on satiation but not on subsequent satiety.

This is another common-sense result: we might eat less of unpalatable foods, but having eaten less, we’re more hungry afterward. And once again, we find that the motivation to stop eating (satiation) is a distinct biochemical process from the satiety (or lack thereof) we feel later on.

Conclusion

Hunger is the interaction of several different clinically measurable, provably distinct biochemical processes—each with its own effects on our brains and bodies. Until we understand this, we are doomed to confusion: fragmentary understanding and incomplete solutions that address only one component of hunger while ignoring the others.

Fortunately, we don’t have to understand the biochemical cascades involved in liking, wanting, satiation, and satiety—because no one does. (These are “active research areas”, which means “we’re still trying to figure all this stuff out”.) Simply understanding these drives on a conceptual level—and why they were selected for in our evolution as humans—can help us navigate the dangerous shoals of dietary advice.

I’ll explore some of these questions in more detail in the upcoming weeks.

Live in freedom, live in beauty.

JS

Continue to Part II, “Hunger Is the Product Of Multiple Perceptions And Motivations, Sometimes Conflicting.”

Did you find this article interesting or illuminating? Share it with the buttons below.

Do you have questions or ideas you’d like to see me address in future articles in this series? Leave a comment!

As I mentioned at the end of last week’s article, I’m taking a week off to enjoy the summer holidays—and the ridiculous snowpack here in the Sierras, which has allowed me three days of excellent skiing in July.

I’ll be back on my regular weekly schedule next week, but in the meantime, it is important to not die.

How Not To Die While Slow-Roasting A Pork Shoulder (Also Known As A “Pork Butt”)

Earlier this year, I decided to slow-roast a pork butt overnight in the oven. After it had been in for several hours, and just as I was falling asleep, my carbon monoxide alarm went off.

This carbon monoxide detector saved my life. Winters are cold where I live. In order to be energy-efficient, I weatherstrip my doors and seal the drafts under them. And since my living area has good solar gain in the daytime, the forced-air heater often won’t come on until very late at night.

Apparently, in a well-insulated home or apartment, a gas oven can produce dangerous amounts of carbon monoxide in just a few hours. And since I was just getting ready to fall asleep, it is very likely that without a working carbon monoxide alarm just outside my bedroom, I would not have awakened the next morning.

At this point, I feel it appropriate to thank my mother (who insisted I have one) and the Kidde corporation (whose product still functioned correctly, even past the end of its advertised 5-year service life) for saving my life.

And because being alive is important, I strongly recommend that everyone own a carbon monoxide detector.

Yes, you’ll be irritated when it gives you that “low battery” chirp every nine months or so, and you’ll be annoyed that the batteries don’t last nearly as long as those in your smoke detectors.

You’ll also be alive.

You should be able to find carbon monoxide alarms at your local hardware store. However, if you’d like to support gnolls.org, you can buy them through the following Amazon links. (Plus, in my experience, Amazon is cheaper.)

Available models have changed somewhat since I bought mine: the most recent “Nighthawk” models come with a 7-year guarantee and are UL listed. And as a bonus, they come with batteries!

Here’s the basic unit: Kidde KN-COB-B-LS Carbon Monoxide Alarm. $23 as of this writing.

And here’s the next model up, which has a digital display that shows the actual CO level: Kidde KN-COPP-B-LS Carbon Monoxide Alarm. $35 as of this writing.

(Note that natural gas or propane heater malfunctions can also result in carbon monoxide poisoning, even if you have electric appliances. And a wood or pellet stove can get you if the flue clogs or the vents leak.)

How Not To Die While Riding A Mountain Bike

During the early season, there are often trees down on the trail—especially after spring storms.

Just a few days ago, I was riding a trail for the first time this year. In the middle of a fast and overgrown section with poor sight lines, I suddenly encountered a small fallen tree, whose sharp, splintered end was aimed directly at my chest.

If I had been going fractionally faster, or been paying less attention, this would have had my corpse stuck to the end of it. I don’t think I’ve ever stopped a bicycle quite that fast—and the sharp end still ripped my glove and cut my fingers as it pushed past, stopping about four inches from my heart.

The moral of this story: Don’t override your line of sight, even on a familiar trail. And always keep your braking system properly adjusted and maintained. Someday you may need every last Newton of force it can provide.

Live in freedom, live in beauty.

JS

Anyone who makes a serious effort to understand the science behind nutrition will understand immediately that news items—most of which simply reprint the press release—are usually pure baloney. In order to learn anything interesting, we require access to the papers themselves.

Unfortunately, that’s not the end of the shenanigans. Abstracts and conclusions often misrepresent the data. Data is selectively reported to omit negatives (for example, statin trials trumpet a decrease in heart disease while intentionally failing to report all-cause mortality). And experiments are often designed in such a way as to guarantee the desired result.

Is there any way to deal rationally with the unending onslaught?

This approach, though satisfying, is discouraged by our legal system. How To Get The Results You Want

First, I’ll walk through a few examples of studies carefully designed to produce a result opposite to what happens to all of us in the real world. Please note that I am not accusing anyone of scientific fraud! What I’m showing is that you can ‘prove’ anything you want if you set up your conditions and tests correctly, and choose the right data from your results.

Example 1: Quit While You’re Ahead

Public Health Nutrition: 7(1A), 123–146

Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity

BA Swinburn, I Caterson, JC Seidell and WPT James

This paper, which purports to be an objective review of the evidence, claims with a straight face that “Foods high in fat are less satiating than foods high in carbohydrates.”

Wait, what?

The authors cite two sources. One is a book I don’t have access to. The other is:

Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995 Sep;49(9):675-90.

A satiety index of common foods.

Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E.

“Isoenergetic 1000 kJ (240 kcal) servings of 38 foods separated into six food categories (fruits, bakery products, snack foods, carbohydrate-rich foods, protein-rich foods, breakfast cereals) were fed to groups of 11-13 subjects. Satiety ratings were obtained every 15 min over 120 min after which subjects were free to eat ad libitum from a standard range of foods and drinks. A satiety index (SI) score was calculated by dividing the area under the satiety response curve (AUC)…”

Only the abstract is available online, but here’s the list of foods they tested, each with its measured ‘satiety index’—from which we find the surprising ‘facts’ that oranges and apples are more satiating than beef, oatmeal is more satiating than eggs, and boiled potatoes are 50% more satiating than any other food in the world!

This is obviously nonsense…but what’s going on here?

Upon reading the abstract, we can see the problem right away: they only measured satiety for two hours! Last I checked, it was more than two hours between breakfast and lunch, or between lunch and dinner. In fact, if you have any sort of commute, two hours doesn’t even get you to your morning coffee break! And given that a mixed meal of protein, carbohydrate, and fat hasn’t even left your stomach in two hours, we can see that this data does not support the breathtakingly bizarre conclusion drawn by Swinburn et. al.

In fact, it’s hard to see what conclusion this study supports beyond “when you don’t let people drink any water with their food, foods that are mostly water take up much more room in their stomach.” This is why oatmeal makes you feel so full…

…for about two hours, until the glucose is all absorbed and your sugar high wears off.

To see what happens when you track oatmeal vs. eggs for more than two hours, you can read the exhaustively-instrumented study in How “Heart-Healthy Whole Grains” Make Us Fat.

Example 2: Construct an Artificial Scenario

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol 61, 960S-967S

Carbohydrates, fats, and satiety.

BJ Rolls

“Fat, not carbohydrate, is the macronutrient associated with overeating and obesity…Although more data are required, currently the best dietary advice for weight maintenance and for controlling hunger is to consume a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet with a high fiber content.”

Really? And what evidence are we supporting this with?

“The most direct way to assess how these differences in post-ingestive processing affect hunger, satiety, and food intake is to deliver the nutrients either intravenously on intragastrically. Such infusions ensure that taste and learned responses to foods will not influence the results. Thus, to examine in rnore detail the mechanisms involved in the effects of carbohydrate and fat on food intake, we infused pure nutrients either through intravenous or intragastric routes.”

And the author goes on to cite her own study to that effect, found here:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol 61, 754-764

Accurate energy compensation for intragastric and oral nutrients in lean males.

DJ Shide, B Caballero, R Reidelberger and BJ Rolls

There’s only one problem with this theory: I don’t eat via intravenous or intragastric infusion, and neither do you.

Physiol Behav. 1999 Aug;67(2):299-306.

Comparison of the effects of a high-fat and high-carbohydrate soup delivered orally and intragastrically on gastric emptying, appetite, and eating behaviour.

Cecil JE, Francis J, Read NW.

“When soup was administered intragastrically (Experiment 1) both the high-fat and high-carbohydrate soup preloads suppressed appetite ratings from baseline, but there were no differences in ratings of hunger and fullness, food intake from the test meal, or rate of gastric emptying between the two soup preloads.”

That’s what the Rolls study above also found. Yet…

“When the same soups were ingested (Experiment 2), the high-fat soup suppressed hunger, induced fullness, and slowed gastric emptying more than the high-carbohydrate soup and also tended to be more effective at reducing energy intake from the test meal.”

Oops! Apparently when you eat fat (as opposed to injecting it into your veins or stomach), it is indeed more satiating than carbohydrate. Raise your hand if you’re surprised.

Example 3: Confound Your Variables

Am J Clin Nutr December 1987 vol. 46 no. 6 886-892

Dietary fat and the regulation of energy intake in human subjects.

Lauren Lissner, PhD; David A Levitsky, PhD; Barbara J Strupp, PhD;

“Twenty-four women each consumed a sequence of three 2-wk dietary treatments in which 15-20%, 30-35%, or 45-50% of the energy was derived from fat. These diets consisted of foods that were similar in appearance and palatability but differed in the amount of high-fat ingredients used. Relative to their energy consumption on the medium- fat diet, the subjects spontaneously consumed an 11.3% deficit on the low-fat diet and a 15.4% surfeit on the high-fat diet (p less than 0.0001), resulting in significant changes in body weight (p less than 0.001). A small amount of caloric compensation did occur (p less than 0.02), which was greatest in the leanest subjects (p less than 0.03). These results suggest that habitual, unrestricted consumption of low- fat diets may be an effective approach to weight control.”

This study looks much more solid at first glance: test subjects were given prepared foods which theoretically differed only in fat content, and which were theoretically tested to have equal palatability. Let’s take that at face value for the moment, and ask ourselves: why were they eating more on the high-fat diet?

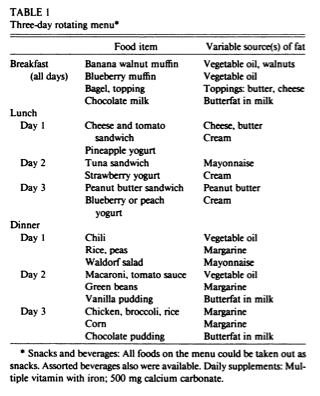

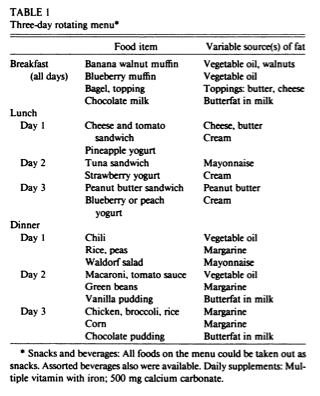

First, let’s look at what made the diet “high-fat”. They helpfully list the ingredients added to each meal to make it higher in fat in Table 1.

Notice what’s been added in the right column? I see a lot of n-6 laden “vegetable oil” (store-bought mayonnaise is made with soybean oil) and margarine. Since this study was done back in 1987, the margarine would be absolutely loaded with trans fats, which we now know are strongly associated with obesity, heart disease, inflammation, and…disrupted insulin sensitivity. (Research review.)

So they’re testing what happens when carbohydrates are replaced primarily with seed oil and trans fats—which makes this study irrelevant to anyone considering a healthy diet.

Second, we have the problem that both breakfast and lunch were served in unitary portions.

“All foods, including those served as units (eg, muffins, sandwiches), could be consumed entirely or in part. … Sandwiches were available in whole or half units.”

Though the study doesn’t say explicitly, it’s probably a good assumption that the higher-fat versions contained far more calories, since the researchers tried to make them as similar as possible in appearance. It’s well-known that offering people larger portions causes them to eat more…especially since unlike breakfast and dinner (which were eaten in the laboratory), lunch was taken out. (If you take a sandwich with you, what are the odds you won’t finish it that afternoon, regardless of size?)

That’s not the worst part, though. The worst part is that their data is completely worthless because of interaction between the different diets!

Normally, controlled trials are done on separate, statistically matched groups of subjects, in order to make sure that effects from one treatment don’t bleed over into another.

However, in some cases, “crossover trials” are conducted, where each group is given each treatment in sequence—separated by a “washout period” that is supposed to let any effects of the previous treatment dissipate. This is less desirable (how do you know all the effects have ‘washed out’?), and is usually done because it allows the experimenters to screen and follow a smaller group.

However, Lissner et. al. didn’t even follow a crossover protocol. Instead, they employed a complicated “latin square” design, in which each test subject consumed a different meal type each day! A typical subject would consume a low-fat meal one day, a high-fat meal the next, a medium-fat meal the third day, and the sequence would repeat.

Can you imagine a drug trial where patients took one drug on odd days, and another drug on even days? How could you possibly disentangle the effects?

All of us have eaten a huge dinner and not been hungry the next morning…or gone to bed hungry and been ravenous when we awakened. In this insane design, each high-fat meal was guaranteed to be surrounded by two days of lower-fat meals. Yet in Figure 2, they graph energy intake for each day as if it were the same people eating each diet for two weeks!

In conclusion, this study is triply useless: first, due to using known industrial toxins for the “high-fat” diet, second, due to unequal portion size, and third, due to an intentionally broken design that commingles the effects of the three diets.

Holding Back The Ocean

The purpose of this article—and of gnolls.org—isn’t to debunk silly press releases, misleading websites, or even misleading scientific papers. I’ve given you some useful debunking weapons for your arsenal, but they’re not enough—because trying to dodge every slice of baloney thrown at us on a daily basis is like trying to hold back the ocean with a blue tarp and some rebar.

The usual strategy is to find a belief we like and stick with it, regardless of the evidence—but that way lies zealotry. What we need is a higher level of understanding. We need knowledge that lets us rationally dismiss the baloney and junk science, while conserving our time and attention for the few nuggets of real, new, important information.

We need to understand how human bodies work.

In other words, we need to understand ourselves.

We need to understand the basics of human biology and chemistry, how it was shaped from ape and mammal biology and chemistry, and how much it shares with all Earth life. We need to understand our multi-million year evolutionary history as hunters and foragers, how we were selected for survival on the African savanna, and how that selection pressure turned little 80-pound apes into modern humans.

And once we’ve used this understanding to answer basic questions like "How is food digested?" and "How are nutrients converted into energy?", we can use those answers to dismiss the baloney and junk science, allowing us to spend our valuable time and attention on real information. Because while it’s blindingly obvious to anyone who’s tried both that eating eggs for breakfast is more satiating than eating a bagel, it’s important to know why.

Conclusion: There Is No Easy Way, But There Is A Better Way

“Here’s a study that says so” isn’t a reason: it’s just a set of observations. We need to know how our bodies work. Only then can we rationally judge the meaning of these observations.

There is no shortcut to this knowledge. If there were one, and I knew it, I would already have told you. The best I can do is to continue to hone my own understanding—and I’ll continue to share what I know (or think I know) with you.

Live in freedom, live in beauty.

JS

As this upcoming weekend is a holiday, I may not have time to write an article for next week.

In the meantime, you can occupy yourself with my “Elegantly terse”, “Utterly amazing, mind opening, and fantastically beautiful”, “Funny, provocative, entertaining, fun, insightful” novel, The Gnoll Credo. (More effusive praise here, and here.) It’s a trifling $10.95 US, it’s available worldwide, and you can read the first 20 pages here.

The world is a different place after you’ve read The Gnoll Credo. It will change your life. This is not hyperbole. Read the reviews.

Did you find this article useful or inspiring? Don’t forget to use the buttons below to share it!

|

“Funny, provocative, entertaining, fun, insightful.”

“Compare it to the great works of anthropologists Jane Goodall and Jared Diamond to see its true importance.”

“Like an epiphany from a deep meditative experience.”

“An easy and fun read...difficult to put down...This book will make you think, question, think more, and question again.”

“One of the most joyous books ever...So full of energy, vigor, and fun writing that I was completely lost in the entertainment of it all.”

“The short review is this - Just read it.”

Still not convinced?

Read the first 20 pages,

or more glowing reviews.

Support gnolls.org by making your Amazon.com purchases through this affiliate link:

It costs you nothing, and I get a small spiff. Thanks! -JS

.

Subscribe to Posts Subscribe to Posts

|

Gnolls In Your Inbox!

Sign up for the sporadic yet informative gnolls.org newsletter. Since I don't update every day, this is a great way to keep abreast of important content. (Your email will not be sold or shared.)

IMPORTANT! If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your spam folder.

|