(This is a multi-part series. For the index, click here.)

How did we get from this:

To both this…

And this?

That’s more than a tripling of brain size—and an astounding increase in cultural complexity—in under 3 million years.

I’ve previously written about the currently accepted explanation, in this article: “Why Humans Crave Fat.” Here are a few bullet points:

- Chimpanzees consume about one McDonalds hamburger worth of meat each day during the dry season—mostly from colobus monkeys, which they hunt with great excitement and relish.

- Kleiber’s Law states that all animals of similar body mass have similar metabolic rates, and that this rate scales at only the 3/4 power of size. Therefore, in order for our brains to grow and use more energy, something else had to shrink and use less energy.

- It takes a much larger gut, and much more energy, to digest plant matter than it does to digest meat and fat. This is why herbivores have large, complicated guts with extra chambers (e.g. the rumen and abomasum), and carnivores have smaller, shorter, less complicated guts.

- The caloric and nutritional density of meat allowed our mostly-frugivorous guts to shrink so that our brains could expand—and our larger brains allowed us to become better at hunting, scavenging, and making tools to help us hunt and scavenge. This positive feedback loop allowed our brains to grow from perhaps 400cc (“Lucy”, Australopithecus afarensis) to over 1500cc (late Pleistocene hunters).

- In support of this theory, the brains of modern humans, eating a grain-based agricultural diet, have shrunk by 10% or more as compared to late Pleistocene hunters and fishers.

(For a more detailed explanation, including links, references, and illustrations, read the original article.)

The Teleological Error

When discussing human evolution, it’s easy to fall into the error of teleology—the idea that evolution has a purpose, of which intelligence (specifically, self-conscious intelligence recognizable to our modern philosophical traditions, and producing something recognizable to us as ‘civilization’) is the inevitable expression and end result.

Geology and archaeology proves this is not so. For instance, 140 million years of saurian dominance (far more than the 65 million years mammals have so far enjoyed) apparently failed to produce any dinosaur civilizations: they simply became bigger, faster, and meaner until the K-T asteroid hit.

Likewise, the increased availability of rich, fatty, nutrient- and calorie-dense meat (enabled in large part by the usage of stone tools to deflesh bones, first practiced by our ancestors at least 2.6 million year ago, or MYA) does not, by itself, explain the over threefold increase in human brain size which began with the Pleistocene era, 2.6 MYA. When a climate shift brings more rain and higher, lusher grass to the African savanna, we don’t get smarter wildebeest, or even larger wildebeest. We get more wildebeest. Neither does this increase in the prey population seem to produce smarter hyenas and lions…it produces more hyenas and lions.

Contrary to their reputation, spotted hyenas are excellent hunters, and kill more of their own prey than lions do. (Many “lion kills” were actually killed by hyenas during the night—whereupon the lions steal the kill, gorge themselves, and daybreak finds the hyenas “scavenging” the carcass they killed themselves.) One 140-pound hyena is quite capable of taking down a wildebeest by itself.

So: if the ability to deflesh bones with stone tools allowed australopithecines to obtain more food, why didn’t that simply result in an increase in the Australopithecus population? Why would our ancestors have become smarter, instead of just more numerous?

The answer, of course, lies in natural selection.

Natural Selection Requires Selection Pressure

I don’t like the phrase “survival of the fittest”, because it implies some sort of independent judging. (“Congratulations, you’re the fittest of your generation! Please accept this medal from the Darwinian Enforcement Society.”)

“Natural selection” is a more useful and accurate term, because it makes no explicit judgment of how the selection occurs, or what characteristics are selected for. Some animals live, some animals die…and of those that live, some produce more offspring than others. This is a simple description of reality: it doesn’t require anyone to provide direction or purpose, nor to judge what constitutes “fitness”.

“Natural selection” still implies some sort of active agency performing the selection (I picture a giant Mother Nature squashing the slow and stupid with her thumb)—but it’s very difficult to completely avoid intentional language when discussing natural phenomena, because otherwise we’re forced into into clumsy circumlocutions and continual use of the passive voice.

(And yes, natural selection operates on plants, bacteria, and Archaea as well as on animals…it’s just clumsy to enumerate all the categories each time.)

Finally, I’m roughly equating brain size with intelligence throughout this article. This is a meaningless comparison across species, and not very meaningful for comparing individuals at a single point in time…but as behavioral complexity seems to correlate well with brain size for our ancestors throughout the Pleistocene, we can infer a meaningful relationship.

Therefore, we can see that “The availability of calorie- and nutrient-rich meat allowed our ancestors’ brains to increase in size” is not the entire story. The additional calories and nutrients could just as well have allowed us to become faster, stronger, or more numerous. For our ancestors’ brain size to increase, there must have been positive selection pressure for big brains, because big brains are metabolically expensive.

While at rest, our brains use roughly 20% of the energy required by our entire body!

In other words, the hominids with smaller brains were more likely to die, or to not leave descendants, than the hominids with larger brains.

What could have caused this selection pressure?

Ratcheting Up Selection Pressure: Climate Change and Prey Extinction

Just as “natural selection” is simply a description of reality, “selection pressure” is also a description of reality. It’s the combination of constraints that cause natural selection—by which some animals live, some die, and some reproduce more often and more successfully than others.

The selection pressure applied by one’s own species to reproductive choices—usually mate choice by females—is often called “sexual selection.” Sexual selection is, strictly speaking, part of natural selection, but it’s frequently discussed on its own because it’s so interesting and complex.

In this essay, I’m speaking primarily of the non-sexual selection parts of natural selection, for two reasons. First, because this article would expand to an unreadable size, and second, because understanding the influence of sexual selection in the Pleistocene would require an observational knowledge of behavior. Lacking time machines, anything we write is necessarily speculation.

In order for selection pressure to change, the environment of a species must change. I believe there are two strong candidate forces that would have selected for intelligence during the Pleistocene: climate change and prey extinction.

The Incredible Oscillating Polar Ice Caps: Understanding Pleistocene Climate

I’ve discussed Pleistocene climate change at length before. (Note: the Pleistocene epoch began approximately 2.6 MYa.)

“Unlike the long and consistently warm eons of the Jurassic and Cretaceous (and the Paleocene/Eocene), the Pleistocene was defined by massive climactic fluctuations, with repeated cyclic “ice ages” that pushed glaciers all the way into southern Illinois and caused sea level to rise and fall by over 100 meters, exposing and hiding several important bridges between major land masses.” –“How Glaciers Might Have Made Us Human”

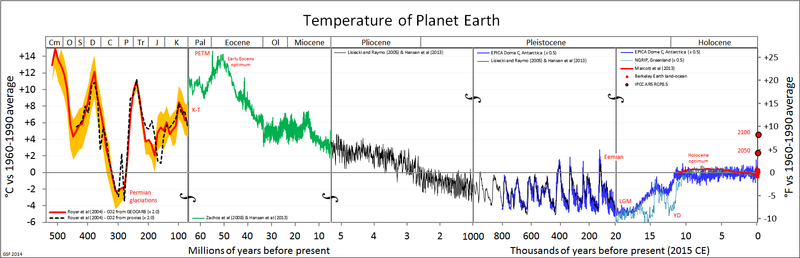

Here is a chart of the estimated average surface temperature of the Earth, starting 500 MYA and ending today. Note the logarithmic time scale!

To appreciate the magnitude and severity of Pleistocene climactic oscillation, note the tiny dip in temperature towards the right labeled “Little Ice Age”. This minor shift froze over the Baltic Sea and the Thames River, caused Swiss villages to be destroyed by glaciers, wiped out the Greenland Norse colonies, and caused famines in Europe which killed from 10% to 33% of the population, depending on the country.

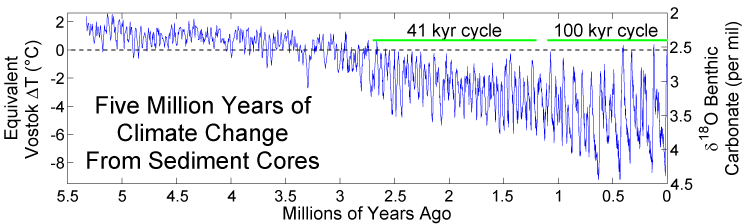

Furthermore, the climate was changing very quickly by geological standards. Let’s zoom in on the Quaternary period (2.6 MYA – present), of which the Pleistocene forms the overwhelming majority (up to 11,800 years ago):

Note that massive 41,000 year climactic oscillations, each far greater than the Little Ice Age, began approximately 2.7 MYA—and the first known stone tools made by hominids (the Oldowan industry) are dated to 2.6 MYA.

Coincidence? Perhaps not.

Genetic Vs. Cultural Change

The behavior of most animals (and all plants) is primarily determined by genetic factors (“instinct”, “innate behavior”)—so in order to adapt to a changing environment, selection pressure must be exerted over many generations. For a short-lived species which reproduces a new generation ever year, or every few years, it might be possible to adapt to a 41,000 year climate cycle via natural selection.

However, for a long-lived species like humans, with generations measured in decades, genetic change is most likely too slow to fully adapt. We would have had to move in search of conditions that remained as we were adapted to…

…or we would have had to alter our behavior in cultural time, not genetic time.

Culture is the ability to transfer knowledge between generations, without waiting for natural selection to kill off those unable to adapt—and it requires both general-purpose intelligence and the ability to learn and teach. While space does not permit a full discussion of these issues, I recommend the PBS documentary “Ape Genius” for an entertaining look at the differences between modern human and modern chimpanzee intelligence and learning. (And I can’t resist noting that spotted hyenas outperform chimpanzees on intelligence tests that require cooperation: more information here and here, abstract of original paper here.)

You can watch the full video of “Ape Genius” here if you are a US resident. (If not, you’ll have to find a US-based proxy server.)

However, climate change is insufficient by itself to cause the required selection pressure. The overwhelming majority of known species survived these changes—including the glacial cycles of the past 740,000 years which scoured North America down to southern Illinois on eight separate occasions—because they could approximate their usual habitat by moving. Even plants can usually disperse their seeds over enough distance to keep ahead of glaciers.

Therefore, to fully explain the selection pressures that led to modern intelligence, we must look farther…to the consequences of intelligence itself.

Live in freedom, live in beauty.

JS

This series continues! Click here to read Part II.

Since my last update, The Gnoll Credo received yet another stellar review:

“A tale told with simple words that are beautifully put together…The most scathing yet beautiful insights into “civilized” humanity that I have ever seen…This novel made me reconsider my life and make serious, long-term changes that have brought nothing but positive results. That is the sign of a truly powerful book. Reading this novel, you will see the names of fictional characters and places, but you are not reading about them. You are reading about yourself.

My conclusion: must read.” –Steven Gray, “Book Review: The Gnoll Credo”

I don’t advertise or have a donation button: sales of TGC keep gnolls.org alive and updated with fresh, meaty content. In addition to the usual online retailers (Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble), US readers can buy signed copies directly from 100 Watt Press. (Outside the US? Click here for a list of international retailers.)